Aren’t people incredible? Every day, I’m reminded about how unique people are, but our uniqueness is always viewed through the lens of similar things. If there were only one eccentric person in the world, we wouldn’t have the word “eccentric” after all.

Screening participants is about finding those with the right combination of attributes that make them distinct and suitable for your study but also representative of a group of people. Finding just the right “kind of person” for research is tough—it can often be one of the hardest parts of research.

In this article, we’ll take you through the steps we recommend when screening participants for research.

The wrong “Guy”

The wrong “Guy”. Back in 2006, Guy Goma became an overnight celebrity after a case of mistaken identity. He was interviewed live on BBC News TV as an internet expert when, in fact, he was currently an unemployed computer technician who had been at the BBC for a job interview.

His two attributes—being named “Guy” and being at the BBC reception at the right time—led him to be “not the Guy they were looking for,” and the poor guy didn’t realize this until he was live on television (at which point he bravely powered on and answered the questions anyway).

While I can certainly admire his guts on national television, the last thing you want as a researcher is to pick the wrong guy to base your research on.

Researchers often cite the difficulty in finding the right participants as the reason for underpowered studies and the reason businesses often don’t conduct much-needed product or market research. The process can seem difficult, confusing, and time-consuming, but it can actually be straightforward and easy.

Here at Positly, we help researchers find the right participants all the time and would love to share what we’ve learned. Following the steps below will help you conduct more significant research, reduce risk, save money, and save time.

Six steps to screening success

- Define your criteria

- Pick your pool

- Describe your screener or study

- Write and order your questions

- Build your screener

- Testing and sign-off

Step 1. Define your criteria

The attributes of the participants you want in your research could vary from incredibly specific to very broad; however, most research will fall somewhere between the two extremes.

Sometimes, researchers are interested in broad general populations. In these cases, they’re less interested in a specific demographic of behavioral attributes and more interested in having a representative sample of high-quality participants or balancing the sample by an attribute (e.g., political affiliation) to compare in an experiment. Other times, researchers have incredibly niche criteria, which can be hard to recruit for but certainly not impossible.

Why are you screening?

The reason for screening will determine how you screen. Are you screening for reflective feedback? What about being a representative user? Or is it just that they are available? Is it mostly about quality?

Typically, the main two categories relate to the participant’s attributes (e.g., demographics, psychographics, behaviors, etc.) and the quality of the participant (e.g., providing insightful answers, answering honestly, reading carefully).

Fortunately, at Positly, we have a number of existing quality measures that we use to pre-screen quality participants for you, so you don’t have to worry about low-quality participants. We’ll be writing another post about how you can add quality measures yourself if you choose, but for now, let’s look at the participant attributes.

Participant attributes

Get together with your team and list out the attributes of your target participants. It’s like the classic game Guess Who; the attributes make the person. Once you have the attributes, you can narrow them down to the types of criteria you can use to determine those attributes.

For example, an “active email user” could be defined as “sending at least 5 emails per day,” and then they could be asked how many emails they send per day.

Just as important as what you want to see in a participant is what you don’t want to see in a participant. You could exclude people who fall far outside the average user profile (e.g., participants who are too technically literate or not technically literate enough), people who work for competitors, or people who would be considered naive for intervention or assessment (e.g., you are testing CBT therapy, and you want people who haven’t previously used it).

Cost of screening

You’ll need to balance the costs of screening out inappropriate participants, including participants who aren’t necessarily entirely ideal. It can be more expensive to get a perfectly screened group of participants than is worthwhile – you’ll need to make a pragmatic choice here.

A common pragmatic choice is to collect all the data and then split the analysis into subgroups of “most ideal participant” and “less ideal” to examine whether there are even differences—this works only if your sample size is large enough.

Sometimes, the cost of inappropriate participants is very low (e.g., just excluding them from the data or analyzing separately), and sometimes, having a few can even be advantageous. You may be planning to exclude the more extreme participant (e.g., on technical literacy) in your final study. Still, it could be worth including them in your pilot studies to see how questions or tasks may be difficult for the average participant (if they’re more likely to struggle and tell you about it, then you can design better research.

However, sometimes the cost of an inappropriate participant can be very high in effort or money (e.g., longitudinal studies, high incentives, travel costs, editing costs), and other times it could be costs in reputation or failure (e.g., embarrassment in the boardroom, failure to publish).

The tradeoff between how much screening costs and how much benefit you’ll get is something you’ll need to keep in mind throughout this process.

Number of attributes

If you are screening for a single study, ideally, your screener will be less than 10 questions or take less than 2 minutes to complete (including demographics).

Take the time to think about which attributes are really important to you. Also, consider what you can gain from using pre-screened participants initially to narrow the funnel. At Positly, we already pre-screen common demographic attributes so that you can use them for targeting.

If someone is doing the screening task with the expectation that they might then take part in the main study, they will be more frustrated if they get disqualified at the end of a long screener than if they got disqualified earlier on (or didn’t need to be disqualified). Be respectful of participants. They’re helping you, and they are essential to research—treat them with the respect they deserve.

When it comes to the number of attributes that you collect, keep in mind the privacy of potential participants. Don’t collect data points that you don’t plan on using or that could be easily de-identified without their consent.

Balanced, representative and weighted samples

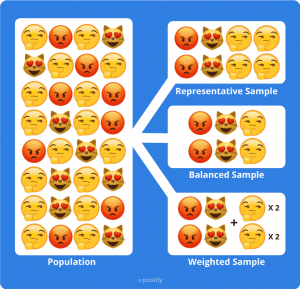

Often, you may need to do more than simply exclude participants entirely based on an attribute; you could be trying to have a certain distribution of attributes in your sample.

If you’re conducting quantitative analysis, you’ll think ahead of time about whether you need to weigh the responses, balance the participants, or match the representativeness of a sample. These are all ways of ensuring that your data will be more meaningful and statistically powerful. Screening for relevant attributes about participants up front will also be required.

The act of balancing your sample is to pick even numbers of different groups so that you can compare them all evenly without having to do any complicated math. For example, I may want 50% PC users and 50% Mac users, or 33% Republicans and 33% Democrats and 33% Other.

Participants may also be selected on the basis that they are representative of a target population; this is often done by stratifying the participants that you recruit into different subgroups with quotas (e.g., Men and Women each by age <50 and 50+) or statistically matching (e.g., ensuring the average age of a group is the same as the target group).

Weighting involves multiplying each participant’s responses by how much their attributes are over-represented or under-represented in the sample. For example, if I wanted a 50% male-female comparison and I only had 20 men and 10 women, I would weight the men’s responses each as 0.5. If you are using weighting alone, you can ask these questions at the end of the study, as they do not determine who is allowed to participate.

Step 2. Pick your pool

The quality and relevance of your participant pool will heavily influence the quality of your research.

In some cases, getting feedback from your friends and family may be a good start and is better than nothing, but in most cases, it’s not going to be very helpful. Friends and family are unlikely to be your ideal participants. Not only are they unlikely to have the right attributes nor be representative, but they’ll also be overly kind to you (e.g., you’ll miss out on the more brutal feedback you need) or sensitive about their privacy (e.g., your friends may not want to share information with you about their lingerie preferences or the state of their mental health).

There are many sites for “exchanging surveys,” where people do each other favors by filling in each other’s surveys (some sites provide “credits” so that your surveys rank higher if you take more surveys yourself). As I am sure many of you can imagine, in most cases, a pool of fellow researchers is not going to be a representative sample—unless you think this looks like a normal person.

Universities and colleges often have participant pools available for their researchers to use. These are primarily student participants who often participate for course credit or as a requirement of their course. While this makes in-person studies easier and can sometimes reduce the cost of paying participants (if it’s a course credit requirement), the student participants are rarely a representative population and are often in high demand, which results in low numbers of participants for researchers.

If you are a company with existing customers, they may sometimes make good participants. If you pick the right people, they could be representative of your customer base (although not necessarily your potential new customers). You’d need to go to lengths to ensure that you get quality responses. For example, ensure that you provide anonymity for their responses and that you don’t provide an incentive so large that you get non-representative customers (just give everyone a fair payment/gift certificate/credit). Furthermore, suppose you are looking to study how you may expand your customer base (e.g., new products, marketing strategy). In that case, your existing customers may not be representative of non-customers – after all, they already use your product or service.

In addition to customer bases, there may be other places where you can find a near-perfect audience. For example, if you are studying soccer players, you could partner with a soccer club or soccer association.

These considerations are why we find it’s often best to (a) pay someone a clear and fair amount that’s enough to appreciate their time but not too much to incentivize bad behavior; (b) recruit from a neutral and broad audience (e.g., micro-tasking, research panels, classifieds, advertising, relevant partners); (c) pre-screen for quality and basic demographics; and finally (d) adjust for representativeness.

We built Positly to help find high-quality research participants who don’t have the common drawbacks mentioned above in some of these methods.

Step 3. Describe your screener or study

When building and publishing your screener, you’ll need to have an appropriate description of your screening study and a description of your main study where it makes sense.

In some cases, you only need to describe the screener. This could be because you don’t want to give away too much until you know who the participants are or because you don’t want to influence their answers. In other cases, it makes more sense to describe the main study so that you only get participants who are likely to continue on to the main study.

In both cases, the screening activity and main study descriptions should include a title and description. Here are some tips for what you could include (not all are always necessary, and sometimes you will intentionally exclude some details to prevent influencing the sample).

- Activity title

- Clear and concise

- Differentiated from other activities

- Relevant to your target participants

- Unlikely to bias the sample

- Activity description

- Description of what’s involved

- Who it is aimed at (where it doesn’t influence answers)

- Participant consent and other ethics requirements (e.g., withdrawal)

- The reason you are doing it

- How many questions there are or how long it will take

The central purpose of these is to find the right audience and avoid influencing that audience in ways that may compromise your study while managing expectations and ensuring that the participant is properly informed to decide if they want to continue.

The title and description are required when posting to Positly (and the same would be required on most other platforms). In many cases, it helps to include them again in the activity itself and ask the participant to confirm before continuing.

In this description, it’s important to be careful about what information you provide and what you withhold. You want the participant to be sufficiently informed, but you also want to avoid influencing the study’s results or providing people the opportunity to self-select by giving things away too early.

However, in some cases where the prevalence of a certain population is low, you may find that you need to be more transparent upfront about what you are after and then use the screener only to confirm that the person is suitable (see this example) – this is called a “transparent screener” and is similar to how recruiting participants in newspaper classifieds used to work.

Step 4. Write and order your questions

Now that you’ve taken the time to think through your criteria, pool and written your screener description, here’s the part most of you have probably been waiting for.

Writing your screening questions

While defining and refining your criteria, you would have a list of attributes for which you need to find questions.

The three main categories of attributes are:

- Demographics

e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, income - Behaviors

i.e., things people do, ways people act - Psychographics

i.e., personality, values, opinions, attitudes, assessments

The way you ask a question can often change the answers you get. Typically, demographic questions are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (e.g., a single person cannot be both aged 25-34 and aged 85-94). Behavioral questions are matters of fact and are often asked using the Five W’s and H (when, what, where, who, why, how), specific numbers (e.g. how many times this month have you eaten an apple?), or selected from lists (e.g., which of these movies do you intend to watch?). Psychographics are often asked using scales, comparisons, and assessments. When asking psychographic questions, it is preferable to use standardized scale formats (such as the Likert scale) or standardized assessments (such as the PHQ-9, IQ, or cognitive reflection test).

Key principles for writing questions

1. KISS: Keep it simple, short, specific

Use simple words and clear sentences. Avoid jargon, technical language, ambiguous words, idioms, and acronyms. Remember that participants are humans. Talk to them like people (and by “talk,” I mean as if you were having a conversation using simple colloquial language).

2. Be precise and accurate

The words you use will matter. They will impact the way people interpret them and, therefore, how they answer them. While you must keep it simple, you must also remain precise and accurate in your questions and answer options.

3. Don’t lead them astray

Ask questions in ways that don’t encourage a specific answer (otherwise, you’ll bias your results from the beginning) – these are called “leading questions,” and they are the devil (in the details) that you must be vigilant to avoid. It shouldn’t be obvious that there is a “right” answer.

4. Be exclusive

Wherever possible, your questions should include all possible options and have no overlap so that people always fit into a single category. In some instances, this may involve including an “other”, “other (specify)”, or “none of the above” options.

5. Don’t be so binary

Often, binary screener questions will tend to give away the “right” answer due to their higher level of suggestibility. Instead, offer multiple options that people can pick from – and if you’re using a multiple-select list (like a checkbox), it’s best to include a decoy (an answer that could not possibly be right) or a limit so that people don’t just select all the options. Suppose you are after someone who has recently watched the Iron Man movie. In that case, I’d suggest asking, “Which of the following movies have you seen recently?” and providing at least one non-existent movie instead of simply asking them yes or no.

6. Tip Responsibly

Sometimes, it can be hard to make a question text sufficiently clear without becoming verbose (and thus backfiring). This is where a tip text on the question itself or explanatory text above the question can help you provide additional clarity without making the question difficult to parse. I still recommend keeping this short and simple – the adage “everything must be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler” seems to fit here.

7. Think global, act local

Remember that we all have different contexts, and some questions simply do not make sense to ask everyone. The internet has been around for a long time. I still occasionally find a store that ships internationally but only accepts 5-digit ZIP codes (US-centric) – they probably wonder why no one buys their products from abroad. Take appropriate steps to customize the questions to be relevant to all participants; this could involve special question logic that changes how you ask a question. However, if you ask the same question in different ways with different people, you’ll need to “think globally” about how you’ll combine the data again at the end.

8. Be entirely random or neatly ordered

The order of your questions will almost certainly have an effect (small or large) on your data. Therefore, it’s important to either (a) follow a “natural ordering” of the options (if one exists) or (b) properly randomize the options for every single participant. For example, options for income or education make sense to have in ascending order, whereas gender and favorite movies can almost always be randomized.

These 8 principles are important to keep in mind when writing any questions, but they’re essential when writing screening questions.

Order your questions

Now that you have a list of attributes and know what questions you want to ask people, you’ll need to decide in what order.

You can easily start by removing anything that you can already determine from the source of recruitment (e.g., the standard demographics offered by a platform or if someone has a Facebook account and you’ve recruited them from Facebook). Then, move anything that is purely for weighting or profiling to the end of the main study.

At this point, you’ll be left with your core qualifying and disqualifying questions. The best way to approach this is to think of it as a funnel. Here are your main goals:

- Identify people who wouldn’t qualify as quickly as possible

- Disqualify early based on obvious blockers (e.g., technical requirements)

- Start broad and then narrow (e.g., “which of these sports do you play?” and only if they select “soccer” ask “how often do you play soccer?”)

- Protect the integrity of all the questions (i.e., don’t give away the “right” answer to a later question in the text of an earlier question)

If you want to nerd out further on question ordering I can recommend this article.

Don’t waste data

Some researchers conduct multiple studies over time, and in many cases, a participant may not qualify for a single study, but they may qualify for a future study. If you or your team plan to conduct a lot of research, you may consider doing omnibus screeners that could qualify people for multiple different studies.

Step 5. Build your screener

By this stage, you should have decided precisely what you’re screening for, how you plan to ask it, and in what order you plan to ask the questions. Now you’re ready to build the screener!

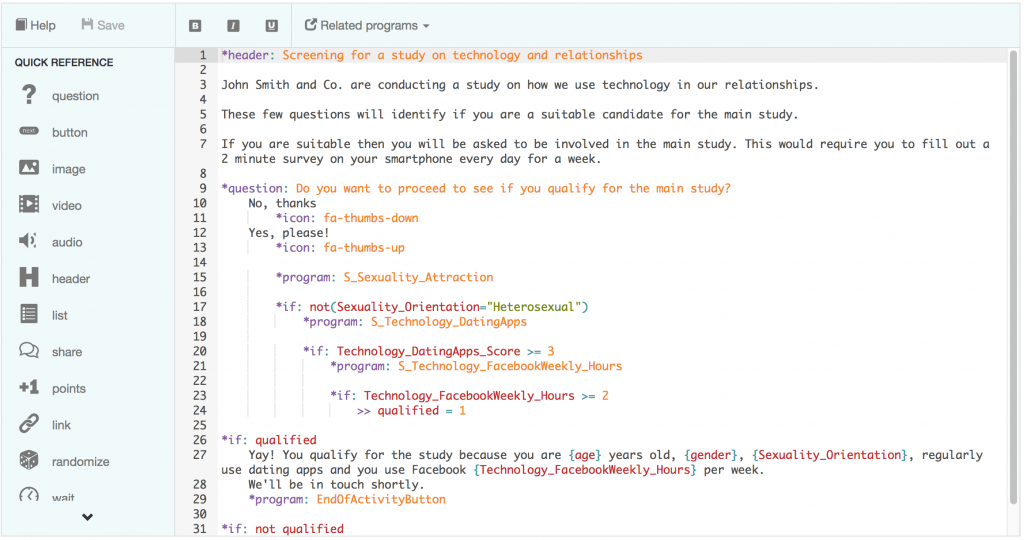

You can use your favorite survey software for this, but I strongly recommend GuidedTrack.

We have built a library of screening questions for you, so all you need to do to get started is include them in your screener and reference the relevant program in GuidedTrack.

To demonstrate how to use the library questions, I’ve made this example screener for you, which is screening for non-heterosexual men aged 25-34 who regularly use dating apps and use Facebook for 2 or more hours a week.

As you can see, all I need to do is introduce the study and then ask a few prebuilt screening questions with a little logic every step of the way. In this case I am combining this screener with the targeting options available in Positly. Because I can already target age and gender I do not need to ask these questions in the screener.

As an added benefit, the participant attributes will be automatically passed through to Positly for use in targeting my main study. This is because I’m using the prebuilt screening question programs and the EndOfActivityButton program in GuidedTrack (if you plan to use Positly and you aren’t using the prebuilt programs, you’ll need to ensure that you include your custom attributes in your end-of-activity link so that you can use them for targeting later).

Step 6. Testing and signoff

At this point, all that’s left to do is test your screener to see if it behaves exactly as you expect it to. Try different combinations and check the process to see that it works.

Once you are confident it works, make sure to check with anyone who may need to sign it off. In academia, this could be an ethics board (IRB), and in a company, this may be a supervisor. The last thing you want to do is find yourself in hot water because you didn’t follow the correct processes or to find your results are unusable because you didn’t screen correctly.

Working alone? It can’t hurt to ask someone else to have a look, especially if it’s your first time.

Ready to launch… and take off!

Give yourself a pat on the back and start adding your screening activity details to your platform of choice (of course, we recommend you use Positly) and launch it. You can then sit back and relax as you watch the data come in, and suitable participants qualify for your main study!